Foreword (Antonis Vradis)

Julia Lurfová’s report is the final product of her engagement with the St Andrews Research Internship Scheme (StARIS) and her collaboration with all other RUL members, which is ongoing. The StARIS Scheme offers the opportunity for undergraduate students to enhance their learning experience by working on academic research projects. Julia’s report also ties into a broader exploration of Third Place under the auspices of the Radical Urban Lab.

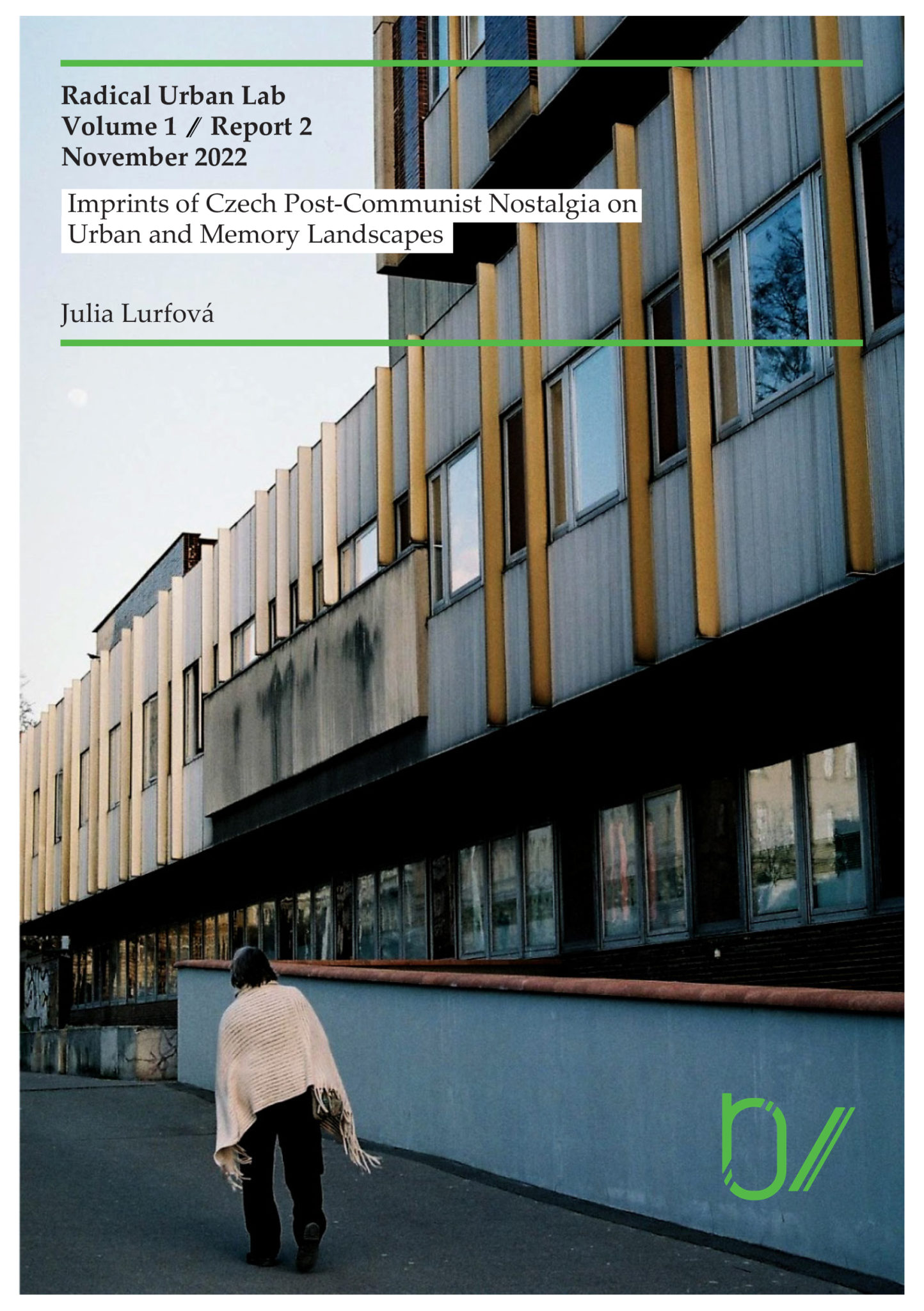

Introducing the case of the Stalin plaza

For a brief period of seven years, an imposing granite monument of the Soviet Union’s Generalissimo, Josef Vissarionovich Stalin, surrounded by archetypes of Soviet and Czechoslovak citizens, towered over the city of Prague. The statue was the winner of a 1949 competition honouring Stalin’s 70th birthday, commissioned by the Czechoslovak communist political party chaired by Klement Gottwald. At the time, Stalin – as Czechoslovakia’s “liberator” from Nazi Germany – was becoming a near-sacred and hence frequently monumentalized figure among communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Eventually finished in 1955, the socialist realist monument of Stalin in Prague became the world’s largest depiction of the Soviet leader. But it did not loom for long. As a result of Khrushchev’s 1956 confidential speech “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences” that heavily criticized the Stalinist regime and provoked a gradual wave of de-Stalinization, the monument was toppled in 1962.

In 1991, a giant red Metronome was erected on the pedestal left bare after Stalin’s statue was demolished by explosives. The Metronome, as a reminder of time’s passage and finiteness, mocks the propagandist narrative of a Soviet-Czech partnership “for all eternity”. Ticking from East to West, the symbol of freedom bridges the two worlds in the newly-independent Czech Republic. Six decades later, in the nation’s collective memory, the place once dominated by Stalin’s monument continues to be strongly associated with the demolished landmark, kept alive through narrative accounts. Nowadays, among Czechs, the term “Stalin” refers to the plaza around the Metronome, turned into a meeting point popular among young people and an open air cultural hub hosting a variety of DJ and film-screening events, beer gardens, and a pop-up bar during the summer months.

The smooth concrete surfaces of the plaza have also been repurposed by the city’s skaters. In 1970s communist Czechoslovakia, skating emerged as an important anti-establishment subculture resisting the totalitarian regime, which recently became the subject of ‘King Skate’, a 2018 documentary directed by Šimon Šafránek. Skating remains pivotal to both Prague’s urban youth culture and to Stalin, “a square with no boundaries and no regulations”. However, the future of skaters at Stalin – and, as a matter of fact, of the public space as a whole – came under threat in September 2019, when the city temporarily closed the plaza in order to structurally refurbish it, while also re-opening a longstanding debate on potential commercial development in the area. Critics of proposals to replace the Metronome with a church or an aquarium have condemned these developments as pathways towards “cultural amnesia”, attempting to erase the contentious yet critically important history of the place within the Czech landscape of memory. Skaters and other Prague locals have since protested the closure and the redevelopment discourse by organising a ‘Save Stalin Plaza’ protest. “[D]on’t touch the genealogy, don’t touch the heritage of this place”, urges urban architect and local skateboarder Martin Hrouda. “Keep it like it is.”